Programmers’ theoretical minimum: array are NOT pointers!

I started use C Language more than ten years ago. However It’s always a lovely surprise when after a lot of time, you can find a good book that teaches you more and more things about a topic that you think to know deeply.

I would tell you about this lovely book: Expert C Programming: Deep C Secrets, written by Peter van der Linden.

This book exposes a lot of C programming language obscurities: declarations, pointers, memory usage, compiling. All things that you need in order to become an advanced C programmer. It’s really a great way to learn something new or reinforce something you know.

In this post I want expose the difference between pointer and array. I’m sure that one of the first things you learned about the C Language is that arrays are the same as pointers. Unfortunately, this is a dangerous half-truth. There is a context in which pointer and array definitions are equivalent. However is wrong think that pointers and arrays can be used in a completely interchangeably.

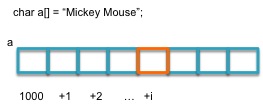

The first step to understand the difference between an array and a pointer is see how they are accessed. When you define an array, the address of the first location, the base address, is known at compile time. This point is extremely important because if you need to use the element at position i, the compiler simply add an offset to the base address. It can do that directly and no extra code is necessary to retrieve the base address first.

That’s why you can equally write these two declaration below:

char a[] = "Mickey Mouse";as well as

char a[100] = "Mickey Mouse";Both declarations indicate that a is an array, namely a memory location where the characters in the array can be found. The compiler doesn’t need to know how long the array is in total, as it merely generates address offsets from the start. To get an element from the array, you simply add the offset to the base address.

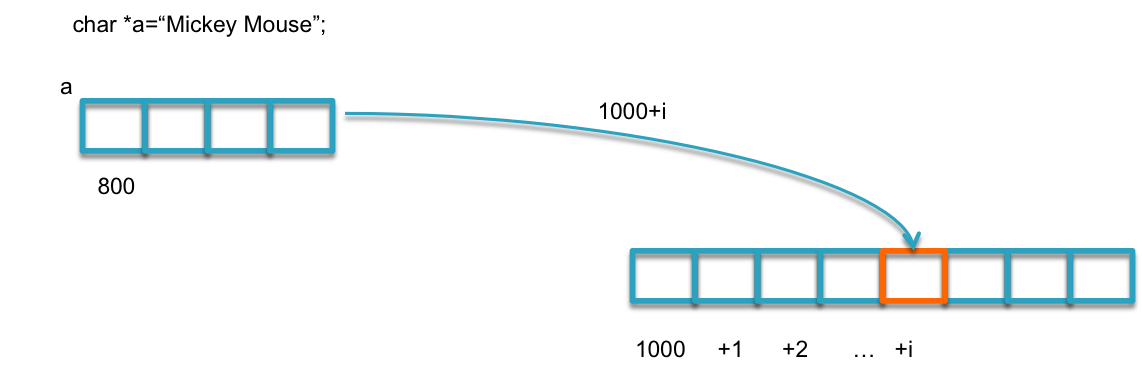

In contrast, the current value of a pointer must be retrieved at runtime before it can be dereferenced (made part of a further look-up).

In contrast, declaring a as a pointer to char means for the compiler that the object *pointed to is a character, not a itself:

char *a = "Mickey Mouse";To get the char, the compiler need to retrive a’s content and then use is as an address to get whatever is there. So pointer accesses are certainly flexible, but at the cost of an extra fetch instruction:

As last thing, I would invite you to see the assembly code produced by my GCC 4.8.1 compiler with this two little examples below:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include "array.h"

int main()

{

char a[]="Mickey Mouse";

printf("\n Hello, %s", a);

return 0;

}#####example_array.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include "array.h"

int main()

{

char *a="Mickey Mouse";

printf("\n Hello, %s", a);

return 0;

}#####example_pointer.c

To output the assembly code is enough add the -S option to GCC compiler. By default, the assembler file name for a source file is made by replacing the suffix .c, .i, etc., with .s.

1

2

e.g.

gcc -Wall -c example_array.c -S

Below are reported the two *.s producted.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

file "example_array.c"

.section .rodata

.LC0:

.string "\n Hello, %s"

.text

.globl main

.type main, @function

main:

.LFB0:

.cfi_startproc

pushl %ebp

.cfi_def_cfa_offset 8

.cfi_offset 5, -8

movl %esp, %ebp

.cfi_def_cfa_register 5

andl $-16, %esp

subl $48, %esp

movl %gs:20, %eax

movl %eax, 44(%esp)

xorl %eax, %eax

movl $1801677133, 31(%esp)

movl $1293973861, 35(%esp)

movl $1702065519, 39(%esp)

movb $0, 43(%esp)

leal 31(%esp), %eax

movl %eax, 4(%esp)

movl $.LC0, (%esp)

call printf

movl $0, %eax

movl 44(%esp), %edx

xorl %gs:20, %edx

je .L3

call __stack_chk_fail

.L3:

leave

.cfi_restore 5

.cfi_def_cfa 4, 4

ret

.cfi_endproc

.LFE0:

.size main, .-main

.ident "GCC: (Ubuntu 4.8.1-2ubuntu1~10.04.1) 4.8.1"

.section .note.GNU-stack,"",@progbits

#####example_array.s

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

.file "example_pointer.c"

.section .rodata

.LC0:

.string "Mickey Mouse"

.LC1:

.string "\n Hello, %s"

.text

.globl main

.type main, @function

main:

.LFB0:

.cfi_startproc

pushl %ebp

.cfi_def_cfa_offset 8

.cfi_offset 5, -8

movl %esp, %ebp

.cfi_def_cfa_register 5

andl $-16, %esp

subl $32, %esp

movl $.LC0, 28(%esp)

movl 28(%esp), %eax

movl %eax, 4(%esp)

movl $.LC1, (%esp)

call printf

movl $0, %eax

leave

.cfi_restore 5

.cfi_def_cfa 4, 4

ret

.cfi_endproc

.LFE0:

.size main, .-main

.ident "GCC: (Ubuntu 4.8.1-2ubuntu1~10.04.1) 4.8.1"

.section .note.GNU-stack,"",@progbits

#####example_pointer.s

As you can see, the two results are very different. In particular, for the second example, the literal string “Mickey Mouse” is allocated by the compiler in the text segment to make it read-only. In contrast, an array initialized by a literal string (e.g. example_array.c) is writable and the individual characters can be changed.

##Further Information

Expert C Programming: Deep C Secrets by Peter van der Linden