Overtake the conventional wisdom around high performance programming

I’ve been thinking on high performance programming for a while. Many domains rely on software systems which are nanoseconds sensitive. Software designers and developers whom build these systems are committed on achieving the maximum throughput and performance boost.

This is not an easy job. It’s hard and requires a huge amount of expertise in several areas. Build such kind of systems is a matter of extremely important choices: from high level architecture and programming languages, down to the cache memory organization and CPU architecture. During my journey among books, blogs, technical papers and conference videos, I went through a really interesting concurrency pattern called Disruptor. LMAX, a trading firm whom proposed this pattern, had built its own core-service with Disruptor, coding everything in Java. These guys have to deal every day with low latency, high reliability, performance optimization an scalability. LMAX trading system can handle over 6 million orders per second on a single thread and on conventional hardware (3Ghz dual-socket quad core Intel on a Dell Server 32 GB RAM). This sounds so interesting to me, so I decided to go deeply to figure out how they reached this amazing result.

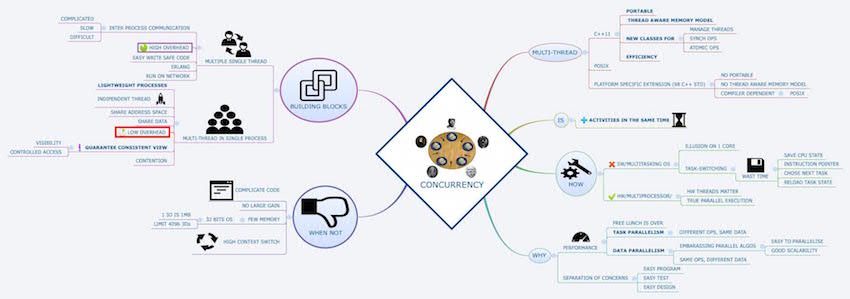

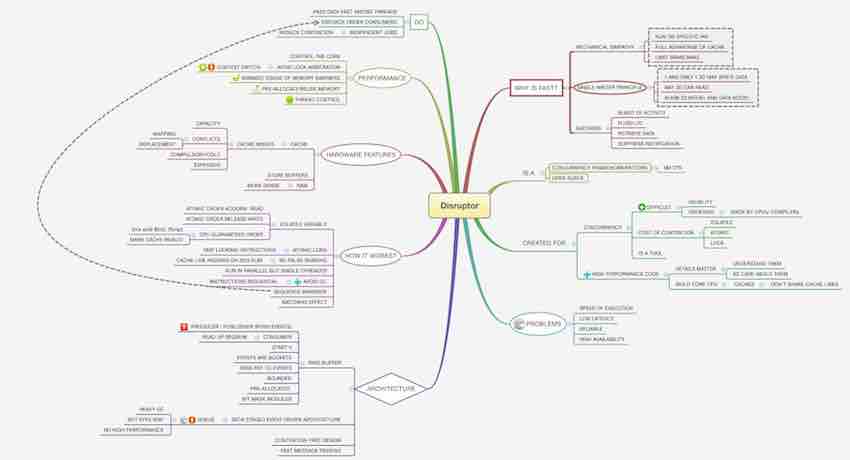

You can easily image that this post is is focused on disruptor pattern. However, this is also the first of many other post on concurrency and high performance computing. As last note, I started to use mind maps for my studies and organizing my notes. I found them pretty good and useful for having a compact representation of a topic. So I attached a couple of the maps I used, hopefully you’ll find them useful too.

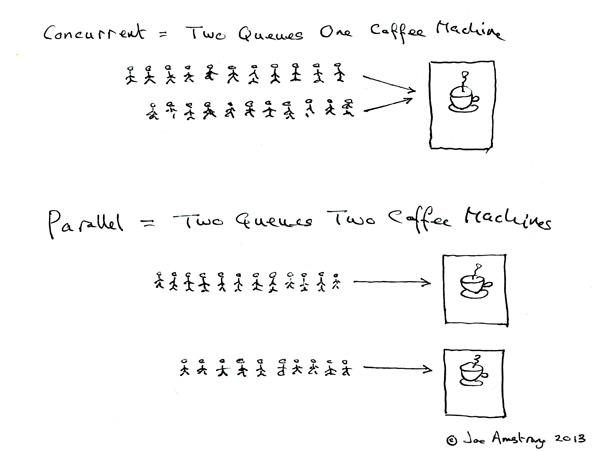

###Concurrency and parallelism Everyone who hear about concurrency and parallelism, have a basic intuition of their meaning: is the ability to do more activities in the same time. In computer programming, this behaviour can be achieved via software and hardware support.

However, before going ahead with this discussion, It worth note to clarify our terminology to avoid confusion. The words parallelism and concurrency are synonyms in many fields, but unfortunately in programming they describe different things.

Intuitively, think the parallelism as a concept more close to hardware than software, while for concurrency the converse happens, because it is more related to programmer’s skills.

A parallel program uses a multiplicity of hardware resources, ie CPU cores, in order to perform computation more quickly. Different parts of the computation are split among different execution unit at the same time, or in parallel, so the output can be delivered quickly. Parallelism is about hard and pure efficiency.

In contrast, concurrency is more a technique for structuring programs that need to interact with many external resources, ie user input, databases, sockets, printers. A concurrency model allows such kind of programs to be modular: everything is organized in multiple threads of control that interact with a single resource, ie a thread for user input, another for printing, another one for database transactions and so forth.

Now, let me spend few words to clarify the terms task, process and thread, the concurrency’s trinity. Despite they are largely used in computer programing, in not unusal to find people that are still confused on their meaning.

A CPU executes a set of instructions loaded in memory. All programmers know that. Well, this set of instructiion is called a task.A process is related to the operating system. It represents an instance of a program that is being executed. In a nutshell, this means that computational resources like CPU, memory, sockets have been reserved for the execution of this program. A thread of execution, or simply tread, is just a flow of instructions executed inside a process.

As software architects and developers, we can build systems that implement task or data parallelisms:

- task parallelism: different operations on the same data,

- data parallelism: the same operation on different chunck of data.

An operating systems (OS) can simulate parallelism also on a single core CPU. This feature is called multitasking. A multitasking OS allows to execute many threads assigning the CPU to each of them only for fractions of seconds (10-100 ms). This frenetic switch among threads is called context switch, and is performed so faster that users have the illusion of a a real multi-core system. In this case we talk of virtual parallelism. Of course context swiching is not for free. To switch is necessary save the current state, ie the instruction and stack pointer, invalidating the cache, choose the next task to perform, reload the new thread in memory, restore the old thread state, and go on.

Only on a multi-core CPU or a multiprocessor computer we have true parallelism. Despite our ability as programmer or how smart our OS is, what’s really matters is how many tasks our hardware supports.

Concurrency and Parallelism, credit Joe Amstrong, http://joearms.github.io, 2013

###Sharing access and visibility As you can image, nowadays concurrency programming is extremely important. Modern applications need to process huge amount of data coming from interconnected networks and wearable technology. CPU performances are not doubling every 18 months like 25 years ago. Quoting Herb Sutter, the free lunch is over.

To have fast software, we need design it to be fast. But this is not enough. We still need well designed software, because they are much easy to program, test and evolve. Last but not least, a well designed software is extraordinary beautiful.

Concurrency is a possible solutions for systems that need process massively quantity of data quickly and nicely scaling on hardware. However, concurrency is not a panacea and is not for free.

Write a concurrent program is much more complicated than writing a single thread one. Multithreading does not necessarily imply a gain in performance. In some situations, the overhead to protect shared data and communication can be not tolerable. Is also necessary an adequate hardware. As example, old 32 bits OS can address ~4GB of memory (~3GB on my old macbook white edition 2007 which is quite old but still perfectly working). Generally operating systems assign 1 MB of memory to every threads, which imply a limit of ~4k threads per system.

“There are other pitfalls; concurrent code that is completely safe but isn’t any faster than it was on a single-core machine, typically because the threads aren’t independent enough and share a dependency on a single resource.” Herb Sutter, chair of the ISO C++ standards committee, Microsoft.

A concurrent program can be developed in two ways: many single-thread processes, or just a multi-thread process.

Programs developed with the first approach are easy to code, but have the disadvantage of requiring a big overhead for inter-process communication. Generally these kind of applications are deployed over a network, were every node run a process.

The second approach is the most used and flexible. A thread is generally called lightweight process and is independent from the others. However, they share the same address space. This can make our life as developers easy and terribly complicated at the same time.

Sharing data makes easy communications among threads, so called ITC (interthread communication), shared data can be accessed by different threads in any order and at any time. Threads can leave common data structures in an inconsistent states, or updates cannot be propagated properly. Sharing access, contention and visibility are the hardest topics to deal with. Special support from programming languages is required to guarantee that only one thread can access sensible data, and protect access during updating operations. Modern languages like Java and C++, offers this features: lock, mutex, condition variables, atomic variables.

Concurrency Mind Map(download)

###Disruptor: a free contention framework

Disruptor is the key component which made London Multi-Asset Exchange (LMAX) incredibly fast.

Technically speaking, it is a fast and efficient way to share data among threads. An interesting story is how the Disruptor has been created. Initially, people at LMAX hadn’t any intention to develop a new framework. However, they realized soon that the mostly adopted architectures like Message Queue, SEDA or Actor, were not good enough for their requirements: low latency, high throughput and reliability.

These guys realized it was necessary deeply investigate into free-lock tecniques, Java memory model and cpu architectures for building something new and achieve the best from all of them. At the end, they reached the conclusion that some conventional wisdom around high performance programming was a bit wrong, so decided to make the Disruptor public. The good news is this framework is completely open source with implementations in Java and C++.

####Ring buffer

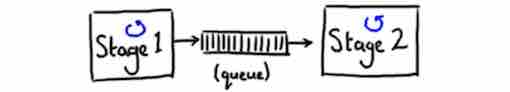

In a multithreading application, queues are the common way to share data among threads. A queue acts as a buffer among different entities, and can be filled and emptied by several entities. This has the advantage of decoupling the entities that put data into the queue, called producers, from the entities that get this data, called consumers. Moreover, a queue is a natural solution to handle burst of traffic, a very common event in trading systems.

Message Queue, credit Trisha Gee

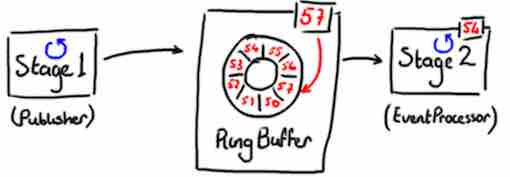

In Disruptor, the queue is replaced by a special circular queue, the ring buffer.

The ring buffer is the data structure used to pass stuff from one thread to another. It is implemented as an array with a pointer to the next available slot, except that there is no pointer to the end of the queue. The only thing used is the next available sequence number, ie 57, which identify the next free slot. This sequence number is increased as more data is added in the ring buffer.

Ring Buffer, credit Trisha Gee

The ring buffer has been chosen to support reliable messaging. Indeed, all data are stored in the same order as they are wrote in the buffer by publishers. However, because of its array-based implementation, it leads a lot of great benefits:

- is faster, ie faster than a linked list

- is simple, ie has a predictable pattern of access

- is fixed size, so can be pre-allocated

- data don’t need to be consumed, ie they stay there until they are over-written

- data are never deleted, so no GC is required

- data are over-written, so memory reuse is encouraged

- is cache-friendly

Because of data are never deleted but over-written, in Disruptor the words Publisher and EventProcessor replace the most commons producer and consumer. This could appear like a negligible difference in terminology, but the fact that data are never deleted helps to understand why this framework is so fast. Different terms help to keep in mind the relevance of this choice.

Publishers and event processors can write and read from the ring buffer in every moment. Despite the first impression, however, the secret of Disruptor is not simply in replacing a queue with a ring buffer. This data structure is at the heart of the pattern, but the cleverness lies in another thing. In particular, the key factor is how is implemented the access controll to the ring buffer.

####Reading into ring buffer

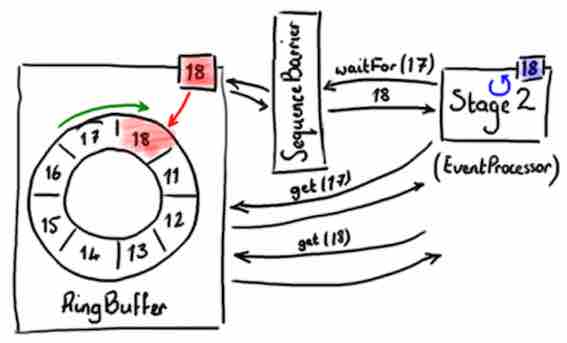

An EventProcessor is the thread that wants to get items from the buffer. As explained before, it is a kind of light consumer except it doesn’t actually remove items from the buffer. An EventProcessor owns its private sequence number, ie 18, similarly the ring buffer.

It does not interact directly with the RingBuffer, instead it uses a DependencyBarrier (called also SequenceBarrier), which is created by the RingBuffer. A DependencyBarrier just returns the highest sequence number available in the ring buffer. The EventProcessor asks the DependencyBarrier to fetch an item and, as it’s fetching them, the EventProcessor is updating its own cursor.

EventProcessor, credit Trisha Gee

####Writing to the ring buffer

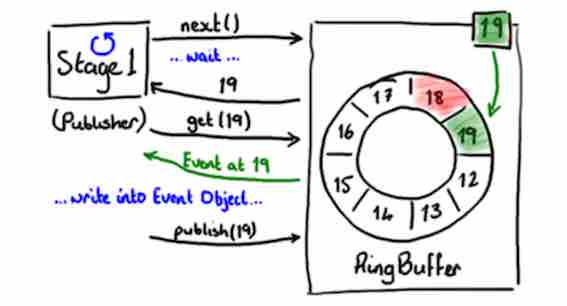

Similarly the consuming side, a PublishPort is created by the ring buffer and the Publisher use it to write to the ring buffer. Obviously, the most important thing is not wrapping the ring. This is exactly what the PublishPort accomplishes.

Writing to the ring buffer involves a two-phase commit. First, the publisher has to claim the next slot on the buffer. Then, when the producer has finished writing to the slot, it will call commit on the PublishPort. The PublishPort makes sure the ring buffer doesn’t wrap by inspecting the sequence number of all EventProcessor that are accessing the ring buffer.

Publisher, credit Trisha Gee

How you can see, the only things trying to get items from the ring buffer can only read them and not write to them, so this can be done without locks. Moreover, the only thing that ever updates a sequence number is that one that owns it.

####All togheter now An event processor trying to get items from the ring buffer, can only read them and not write to them. This operation can be done without locks thanks to the Publishport; it guarantees that the block is not over-written until all consumers have finished with it.

The only component that can update a sequence number is that one that owns it, ie event processor and publisher own their private sequence number.

There is only one place in the code where multiple threads might be trying to update the same sequence number. This is also why each item in the queue can only be written to by one publisher. It ensures there’s no write contention, therefore no need for locks or compare and swap operations (CAS) operation.

At this point, it should start to be clear why Disruptor framework is so fast. It has been developed following the single writer principle, which states that only one thread can write a chunk of data. Having only one writer eliminates the need for contention handling, ie use locks or CAS which are notoriously cpu-expensive. Disruptor is a zero contention framework.

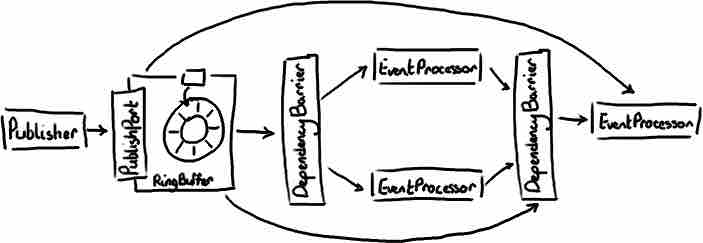

A good advantage of Disruptor is that it can easily be adopted to model real solutions. In picture below, you can see there is one publisher and three event processors, where one of them has a dependency from the others two.

Disruptor, credit Trisha Gee

####Multiple publishers

Not all applications can use a single publisher. Indeed, is not unusual have multiple producers that compete to write to the buffer. In these situation, Disruptor needs to manage contentions, specifically updating the next available sequence number in the case of multiple publishers.

We know locks are slow. They need support by the OS. However, it take time for the OS to arbitrate among several threads that compete among themself. Moreover, the OS might decide the CPU has better things to do than servicing out threads. Moreover, for each call to the OS, there are many undesirable effects that slow down the system, ie flush pipeline, cache invalidation, context switch and so forth.

I explained in previous section that concurrency is hard to implement correctly and effectively: naive code can have unintended consequences. The granularity of protected shared data need be chosen carefully, because selfish code could slow the system down.

“My hypothesis is that we can solve [the software crisis in parallel computing], but only if we work from the algorithm down to the hardware – not the traditional hardware first mentality.” Tim Mattson, principal engineer at Intel.

It’s quite interesting learn how the disruptor address these issues through the use of mechanical sympathy ( Mechanical Sympathy is Martin Thompson’s blog title, one of the guys whom implemented disruptor).

In a nutshell, mechanical sympathy means *understanding how the underlying hardware operates, ie the cpu architecture, and programming in a way that works with that, not against it**.

#####Contention As said before, locks are never used in this framework. Instead, to make sure that operations are thread-safe, Disruptor uses CAS operations, ie defining sequence number as AtomicLong.

A CAS operation is a CPU-level instruction. It doesn’t involve the OS, it goes straight to the CPU. It has the advantage to take less time than using a lock, but more time than a single thread that doesn’t worry about contention at all. Use a CAS is not cost-free, so their use should always be limited as much as possible.

Another solution used in the previous version of Disruptor framework, is based on Memory Barriers, and consists in defining the next available sequence number as volatile.

A Memory Barrier is just another CPU-level instruction that:

- ensure the order in which certain operations are executed

- influence visibility of some data forcing cache refresh.

We know that computers and CPUs try optimize code continuously reordering instructions. Inserting a memory barrier has the effect to tell to both compiler and CPU that what happens before the barrier needs to stay before, and what happens after needs to stay after. The other thing a memory barrier does is force an update of the various CPU caches.

For a volatile variable, in particular, the Java Memory Model puts a write barrier instruction after a write to it, and a read barrier instruction before a read from it. So every update to sequence number is safe and correctly propagated to all publishers with no kind of locks required.

Like CAS, memory barriers are much cheaper than locks. The OS does not need to interfere and arbitrate between multiple threads to solve contentions. However, also in this case, nothing comes for free. Read and write operations on volatile variables are relatively costly and can have a performance impact:

- the compiler/CPU cannot reorder instructions

- high number of cache refresh

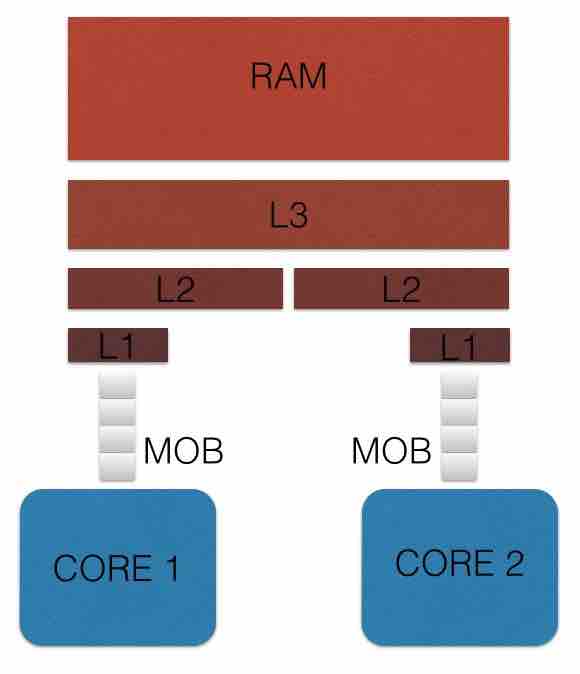

#####False sharing Another kind of problem, a very subtle problem, is the so called false sharing. Before I explain what it is, let’s have a quick look about cache architectures in modern CPUs.

The golden rules about cache is: the closer the cache is to the cpu, the faster it is and the smaller it is. Cache is made up by levels:

- memory ordering buffer (MOB), an associative queue that can be searched for existing store operations, which have been queued when waiting on the L1 cache

- L1 smallest and very fast, it lies right next to the core that uses it;

- L2 is ligthly bigger and slower, but is still only used by a single core;

- L3 is bigger ans lower that L2, and is shared across cores;

- RAM, which is shared across all cores and all sockets.

Cache Memory Architecture

When the CPU is performing an operation, it’s first search in MOB for the data it needs, then L1, then L2, then L3. If the data required is not in any of the cache levels, they need to be fetched from RAM. More levels are crosses, more time the operation will take. Obviously, compiler and cpu try to optimize code making sure that that data is in L1 cache if your application is doing something very frequently,

The cache is made up of lines, typically 64 bytes, and it effectively references a location in main memory. The interesting thing is when we look at what effectively is stored inside a cache line. Not an individual items as expected, ie a single variable or pointer, but it could be many variables, all ones which lie in contiguous memory locations to the data we are interested in.

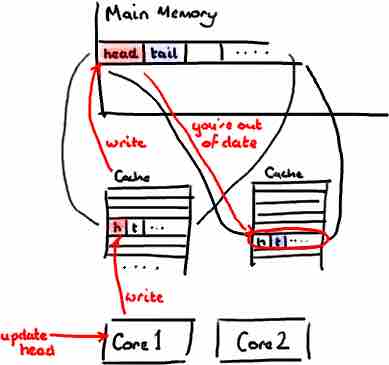

We are close to get the point. Image to have a simple queue. No matter which implementation is chosen, this queue will have tail, head and size variables. There is contention around these varaibles, and perhaps for the entries if a consume operation also includes a write to remove them. tail, head and size variables are often very close in memory and, as a consequence, they will be in the same cache line.

Memory Map of Queue

If you have two threads running on different cores, ie a consumer and a producer, the former could write head while the latter the tail. However, because these variable are in the same cache line, each operation in the consumer that require to update the head will effect the cache line and, as a consequence, it will invalidate the cache line use by the the producer.

False Sharing

This effect is called false sharing. To avoid this, in Disruptor framework all the next available sequence numbers are padded, ie. they are filled with dummy variables to be sure that false sharing can never appear in cache lines.

This is the way Disruptor addresses contention: tracking sequence numbers at independent stages (ring buffer, publishers end event processors), using CAS operations and cache line padding. Below a mind map that describe it.

Disruptor Mind Map(download)

##Further Information

Introduction to the Disruptor, by Trisha Gee, www.slideshare.net

Sharing Data Among Threads Without Contention, by Trisha Gee, Oracle Java Magazine

How does LMAX’s disruptor pattern work?, http://stackoverflow.com

Mechanical Sympathy, Hardware and software working together in harmony, by Martin Thompson

Avoiding and Identifying False Sharing Among Thread, Developer Zone, Intel

C++ Concurrency in Action, by Anthony Williams