Memory models for effective concurrency.

Modern multi-core CPUs are extremely powerful. But not all kind of applications are able to take advantage of this computational power. Indeed, this multicore revolution is a kind of force that pushes towards the adoption of new techniques in concurrent programming. This first part covers the state-of-art, the most used techniques and tools for concurrency. Starting from the fundamentals of concurrency, I’ll show how to take advantage of memory models and the modern CPUs’ architecture for running programs extremely fast. As I hope it will become clear along the discussion, master these concepts is a treasure of extremely useful ideas for programming.

###Facts of a life in programming

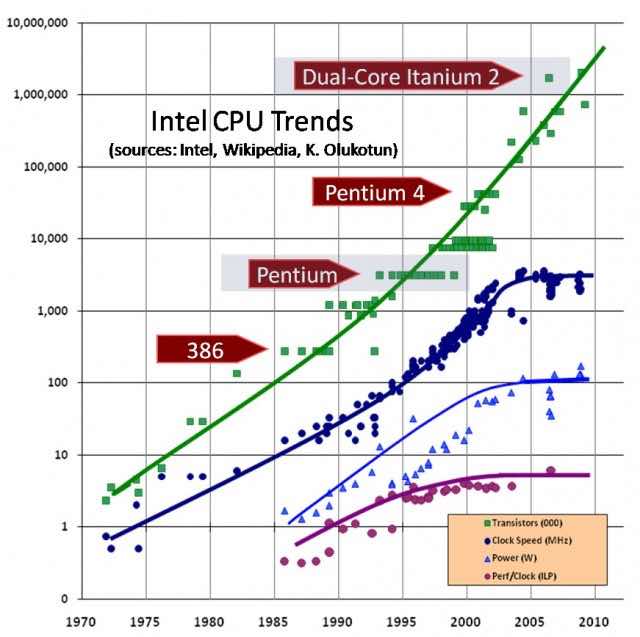

Since ‘70, the advances in semiconductor industry have lead to faster CPUs and a steady growth in speed of execution of sequential programs. This progressive increasing in performance is well know in IT as (Moore’s Law)[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moore%27s_law]. However, during the last decade, the increasing rate is no more as in ‘70. Nowadays, there are lots of technological constraints that limit the performance of individual processor cores. How you can see from the picture below, transistor scaling continued long after IPC while clock speed has essentially flatlined. Actually computer industry is relying increasingly on providing more cores for CPU to improve performance. The architecture of a modern multicore cpu, however, has a limited appeal for single thread application. Indeed, multi-core benefits are only for multi-threaded applications. Paradoxically, a single thread application runs more slowly on a modern CPU than an old Pentium 4, because of the semiconductor industry’s tendency of reducing cores’ speed for less power consumption, and increasing the number of cores inside a single chip. The harsh reality is programs can no longer ride the wave of hardware. They must be designed to be fast.

The harsh reality is programs can no longer ride the wave of hardware. They must be designed to be fast.

Intel CPU Trends

In 2015 software industry is really advanced. We are used to extremely reactive user interfaces on iOS or Android devices, fast query results using Google or Bind, processing big data using analytics platform as BigQuery, or ultra low-latency applications in High Frequency Trading firms. In this contexts, write real fast programs is extremely hard, because requires deep skills in many areas: programming models, data structures, programming languages, compilers, operating system, memory hierarchy and microprocessor architectures. Exploit the power of multi core hardware is one of they keys for building these kind of applications.

As example, try to watch some of the optimization tips suggested by Andrei Alexandrescu in this video. In the core code, replace a smart pointer with a raw pointer to const object as function argument saved a buch of cpu instructions. On a small project, this change is almost irrelevant. However, it had massive impact on their application which runs on thousands on server around the world. If you don’t know, the application is Facebook.

Differently from the past, developers must learn how to code for modern multicore CPUs in a way that lets applications to benefit from the continued exponential growth in performance. At the base of programming there is the idea of composability. The main epochs in the programming are characterized by changes in the way it was possible to compose software entities. We’ve gone from structural programming to object oriented programming (OOP), and now we are witnessing the constant growth of functional languages. Indeed, Java and C++ which represent the essence of OOP, now support lambda functions to reflect the idea of functional programming.

OOP is the prevalent technique in software development. Although it useful in many contexts, it has a very big weak: it does not fit well to concurrent programming and parallelism, but rather encourages the mistakes in the planning and design of low performance due to poor quality.

Indeed, in concurrency all pitfalls are possible (also seeing pink elephants). As software engineer or developer, keep in mind a simple and clear vision on the meaning of concurrency and its impact on system programming. Concurrency is built on three pillars: - responsiveness, ie don’t block, run tasks asynchronously - throughput, ie minimize the time needed for an answer running more tasks and composing intermediate results - consistency, ie ensure the correct access to shared data and avoid corruption

Thinking about it, in OOP the issue lies in its most important feature: information hiding. Information hiding combined with sharing and mutation, is micidial cocktail for program correctness. Whenever two threads try to access the same portion of data, and one of them is going to write, is the programmer in charge of synchronize the access of shared data, otherwise a data race arises. A Data race arises when one thread in a program can potentially write a shared memory location while another concurrently accesses it. Data races are one of the most insidious things in concurrency, because threads can read corrupted data and exhibit randomic behaviour. The use of synchronization mechanisms is required every time the access to shared data is not predictable and therefore must be coordinated.

Modern programming languages offer several tools to prevent data races. Among these, the most famous is probably the lock, which is often used in combination with a mutex. For each thread that wants access shared data, you must first request the exclusive use of that portion of data by acquiring the lock, do the computation and release the lock.

However, locks pose a serious problem when working with large software projects or latency-sensitive applications. The idea to use the lock to protect the data synchronizing access is nice, but unfortunately it does not make a good job in big projects: use lots of them may impact on performanced, ie deadlock or livelock. In a nutshell, locks do not compose. But programming relies on composition: functions, objects, libraries. etc.

As conclusion of this quick overview, it worth mention that there are two major alternatives on the use of locks in concurrency: lock-free programming and transactional memory. The former is about create data structures that use atomic operations and can be shared without an explicit lock. It relies on a detailed knowledge of the memory model (I’ll provide a detailed definition in the next sections) used by the processor. The latter takes the core idea of transactional databases. Programs are written as a series of atomic blocks where each transaction among states is safe.

###The importance of a thread-aware abstract machine

As known to most of you, in every specification of a programming language, ie its main features as syntax and semantics, there is no explicit reference to a specific architecture, ie x86, IA64, Power or ARM, but everything is explained referring to an abstract machine. An abstract machine is nothing more that a convenient generalization view of the underlying hardware, which allows designers to describe the language and provides guideline for writing additional tools, ie parsers, compilers, linkers, optimizers, etc. debugger.

With C++11 many powerful features have been introduced with the aim to make programming easier. Among these new features, the most revolutionary, and in the same also the most silent, is the switching from a single-thread to a multi-thread abstract machine. After about 30 years from the first edition of C++, we finally have a memory model that allows to think enough generically, ie independently from the specific cpu architecture, on how concurrent programs are executed. This is turning point in the history of the language itself, because for the first time we have the support for concurrency in the standard library.

The machine everyone codes for

In older versions, ie C++99 and C++03, the standard defines single-threaded program execution. The standard doesn’t mention threads at all, and compiler were mostly unaware of threads. The abstract machine fully reflects the Von Neumann architecture, which is a rather spartan architecture. Its biggest advantage is in its simplicity because it is very close to how a real machine works. Being a very intuitive architecture, is easy describe the evolving of computations because CPU and RAM are directly connected. In this abstract machine, the programming model is implicitly single-thread.

Although concurrent programming in C++ was done since ‘80, up to 2011 there was no mention in the standard of terms like multithreading, nor atomic operations nor mutex. Most of the concurrent code written until then, was based on threads library, ie POSIX threads or Win32 threads, or with the aid of an intervening layer that provides a platform-neutral interface, ie Boost Threads. The first consequence was, obviously, no-portable code.

The good news is C++ 11 has filled this gap. Such as Java, which has a well specified memory model since Java 5, the C++ memory model is thread aware. The Standard committee did a good job (thanks to Herb and his guys) for providing all essential tools for concurrent programming. There are high level tools, ie mutex and condition variables, and low-level tools, ie atomic operations and memory barriers.

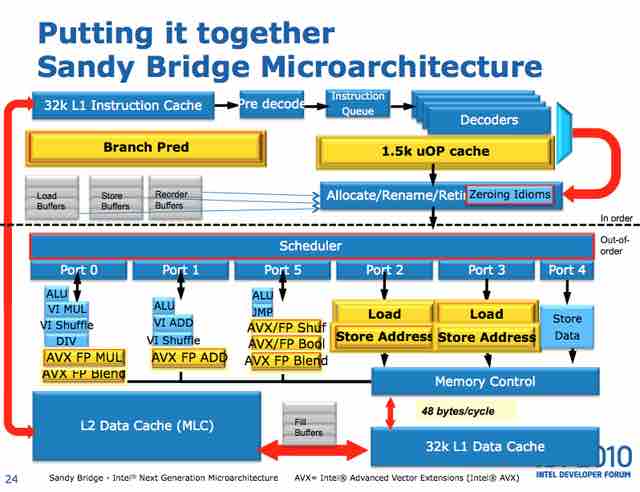

###Multi-core CPUs architecture and code optimization

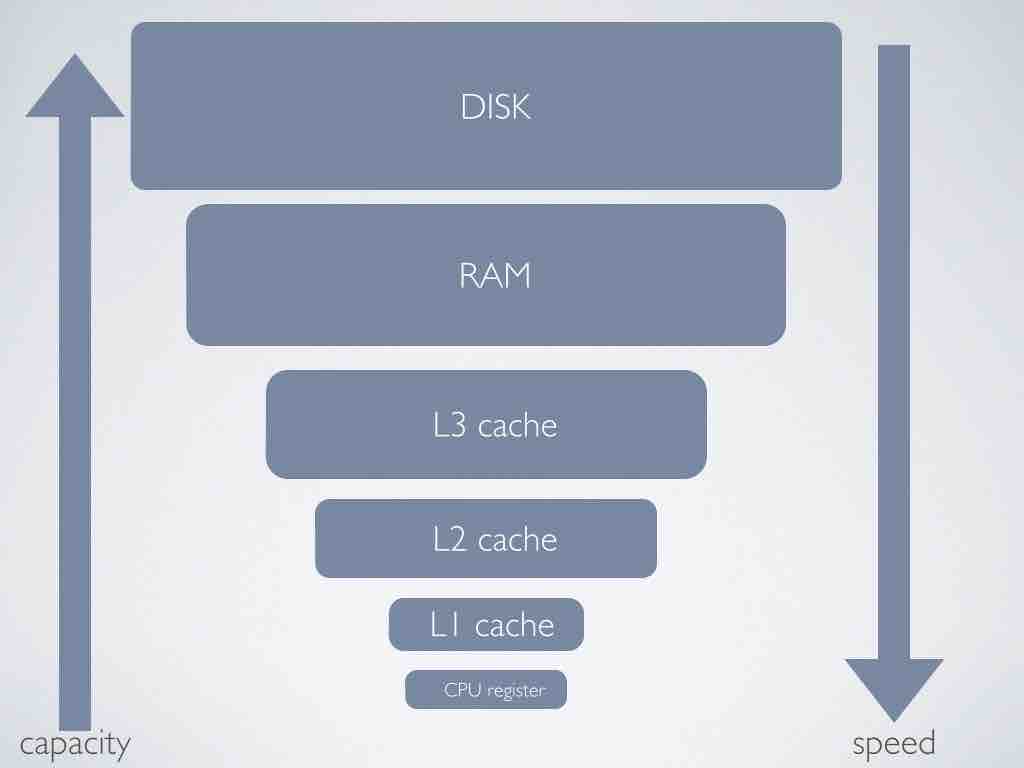

It is unthinkable to program as if we still have to deal with such primitive architectures described above, in which CPU is directly connected to memory. Actually our CPUs have several cores, and memory access is not direct but occurs through a series of levels of caching, generally three. Not to mention other stuff added along the way to improve execution speed: store buffers, branch predictions, pre-fetching, speculation, out-of-order execution, hyper-threading etc,. To quote Herb Sutter, is true that ‘the free lunch is over’, ie core’s GHz are no longer increasing as in the past. However, as explained in the previous paragraph, there is no more free food only for single thread programs. Is a mistake think that CPUs are not getting faster. They never stopped to be faster and faster, but nowadays they are getting fast in a different way.

Cache Memory Architecture

To take advantage of this new form of speed, new paradigms, models, techniques and tools are required. Rethink the way of programming, be hardware aware. In a nutshell, write code that does not run against the hardware, but instead take full advantage of the increasing complexity of CPUs. This is the so called mechanical sympathy, to quote Martin Thompson’s blog title.

Concurrent programming is the way to unlock the power available on modern CPUs. As explained previously, write concurrency code is not easy because it hides several kind of pitfalls. If not correctly applied, you can observe unexpected results (remember the pink elephant), and have long debugging sessions. Data races are the biggest problem. Actually, reading and writing operations are not atomic but are multi-steps, and therefore interruptible at any time, This means that data can be left in inconsistent states. Ensure the correct access order and exclusive ownership in modification can be obtained in several ways, and depending on the techniques used, the impact on performance can be more or less high (note: In an ideal world there would be no data races, but in some cases we can tolerate the existence of benign data races. For more info look at Benign Data Races by Bartosz Milewski).

‘Begin at the beginning’, the King said gravely, ‘and go on till you come to the end: then stop.’ - Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

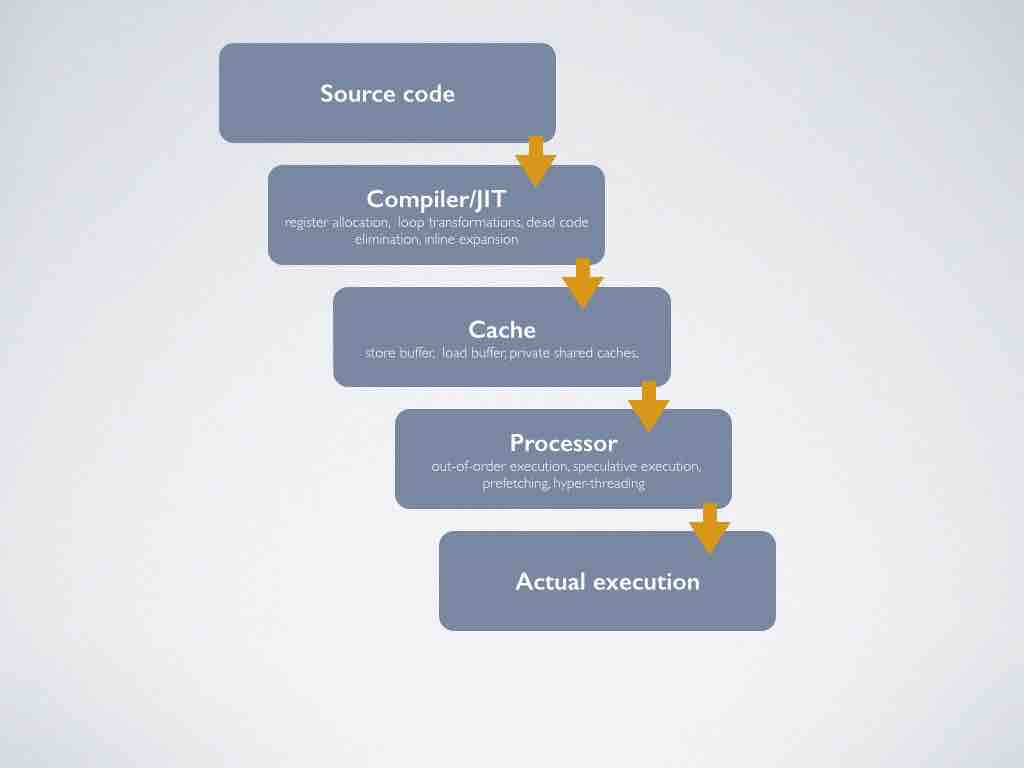

I suppose most of you are aware that programs undergo several transformations, it is optimized, before being executed by CPUs. But unfortunately not all know exactly what type of transformations occur, at which level, and why these transformations are so important on modern hardware. So let’s start from the beginning.

Program optimization

Program optimization involves reorder instructions, add new or remove other ones. Transformations can happen at any level, at the compiler/JIT stage, inside CPU or at cache level. Optimization starts at compiler stage. This is not a case, in fact, the compiler knows all operations in memory and can therefore optimize them. If there are no data races, optimizations are conservative in the sense that the final behavior does not change. However, in multithreading, the compiler does not know what are the memory locations associated with share data. In this case, is the programmer in charge for providing this extra information and avoid unpleasant consequences.

//Can transform this

a = 0;

b = "hello"

a = 1;

// to this

b = "hello"

a = 1;Optimization 1: Elimination of dead code

//Can transform this

if (cond)

a = 42;

// to this

r1 = a;

a = 42

if (!cond)

a = r1;Optimization 2: Speculation

//Can transform this

for (int i = 0; i < max; ++i)

acc += v[i];

// to this

r1 = acc;

for (int i = 0; i < max; ++i)

r1 += v[i];

acc = r1;Optimization 3: Register allocation

//Can transform this

a = 0;

b = "hello";

c = 7.1;

// to this

c = 7.1;

b = "hello";

a = 0;Optimization 4: Reorder

//Can transform this

for (int i = 0; i < row; ++i)

for (int j = 0; j < col; ++j)

acc += m[i,j];

// to this

for (int j = 0; j < col; ++j)

for (int i = 0; i < row; ++i)

acc += m[i,j];Optimization 5: Loop transformation

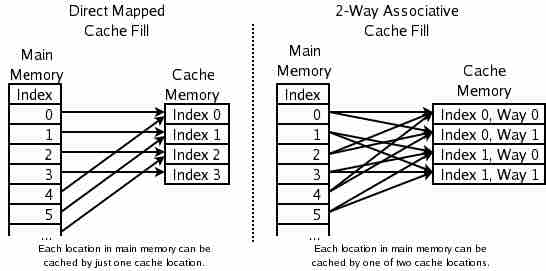

An obvious question is why so many kind of optimization? For a simple reason: speed. Accesses in memory are the slowest operations of a CPU. This is because the difference in performance among CPUs and memories has increased in the last two decades. Actually, with modern caches, the farther you go, the slower you are. TYears ago the semiconductor industry found a solution to fill this gap, and started build CPUs with caches with the aim of reducing the overhead of expensive memory access. Actually modern CPUs have a multi-layer memory hierarchy; consisting of a series of progressively larger and slower caches between the processor and main memory. Typical values are 32 KB L1, 256KB L2, 8MB L3. Each of the individual cores has a dedicated L1 and L2 cache, but the L3 cache is a shared resource.

Intel Sandybridge Architecture

A cache memory is an hash table with fixed size buckets and no chaining, full hardware implemented. The number of lines is a power of 2 as the size of a single cache line. This choice take advantage of the binary arithmetic and make the lookup in the cache extremely fast. In hardware parlance, if the cache has 2N lines, the hash function is extremely simple: extract N bits from the memory address and check the corresponding cache line. The replacement policy is the strategy used to decide in what cache line a particular entry of main memory will go. If any cache line to hold the copy can be chosen, the cache is called fully associative. At the other extreme, if each entry in main memory can go in just one place in the cache, the cache is called direct mapped. Typically caches implement a good compromise in which each entry in main memory can go to any one of N places in the cache, and are described as N-way set associative caches.

Direct Mapped cache and 2-Way Associative cache

Actually the biggest penalty inside a modern CPU is a cache miss, ie data or instructions not present in cache. CPUs do their best to ensure that expensive operations start as soon as possible, and that intermediate results are kept close to points where they are used. If data are not present in cache, a CPU can waste thousands of instruction doing nothing. Program optimizations are made for maximizing the cache hit rate, which is the key to achieve high performance.

Modern CPUs are so faster that a cache of several megabytes cannot keep up with them. Therefore, caches often are partitioned into nearly independent banks, with the aim to allow each bank to run in parallel. Memory normally is divided among the cache banks by address, ie all the even-numbered cache lines might be processed by bank 0 and all of the odd-numbered cache lines by bank 1. However, this hardware parallelism has a dark side: memory operations now can complete out-of-order, which can result in some confusion. Despite a given core always perceives its own memory operations as occurring in program order, memory reordering issues arise when a core is observing other core’s memory operation. For example, consider the simple code below:

bool a = false;

bool stop = false;

//THREAD #1

a = 42;

stop = true;

...

//THREAD #2

while (!stop);

answer = a;

...A possible value for answer is 42. I said ‘a possible value’, because ‘answer’ could be 0 when program ends. Why? Check the code after the optimization made by the compiler:

bool a = false;

bool stop = false;

//THREAD #1

stop = true; //<= reordering

a = 42;

...

//THREAD #2

while (!stop);

answer = a;

...A possible runtime ordering of operations could be (follow the numbers on the right side)

bool a = false; (1)

bool stop = false; (2)

//THREAD #1

stop = true; (5)

a = 42; (6)

...

//THREAD #2

while (!stop); (3)

answer = a; (4)

...The little piece of code was enough to show how is easy putting an undefined behaviour in the code. With code optimization and modern CPUs, things could go crazy.

###Memory Model A memory model helps to sort out the mess created by optimization. In computing, a memory model describes the interactions of threads through shared memory and their use of the data. This definition is taken from Wikipedia, but at first appear does not tell too much.

- What is a MM, exactly?

- What is specified in a MM?

- Why it is so important having one in modern programming language like Java and C++?

Memory models define valid code optimizations inside a system, with the aim to ensure the faster execution on the hardware available without running the risk of introducing a race condition that could lead to undefined behaviour in case of concurrency. It provides sufficient guarantees to the programmer to guard against unexpected transformations that are benign in the absence of threads but change the semantics of a concurrent program.

hardware parallelism has a dark side: memory operations now can complete out of order, which can result in some confusion

Most existing multithreaded C++ applications operate in an environment in which the semantics of data races are left intentionally undefined, ie POSIX threads standard takes this route. As consequence, a program containing a race condition has an undefined behavior.

Memory models are used to turn an undefined behavior in a consistent one. Specify a memory model means provide a guideline on:

- how threads interact with the memory

- which values a read operation can return

- when value updates are visible to the other threads

- what assumptions can be made in accessing memory for new types.

The simplest and strongest memory model is called Strict Consistency. Instructions are executed one by one in the order specified by the programmer when writing code. There is only a simple rule: any read from a memory location X gets the latest written value.

It is a very simple model, easy to program and optimize. Essentially, it has the same semantic as on a single-core processor. C++03 uses this model. The optimized program behaves as if it were written by you: you do not observe the optimizations made by the system. They are not observable. However, is guaranteed that the result of the execution is exactly the same as the original code.

However, as showed above, in a multi-threading environment, optimizations are observable in several threads, leading to erroneous results.

In concurrent programming, the closest model to Strict Consistency is the so called Sequential Consistency, introduced by Leslie Lamport in 1979. It is slightly weaker model than strict consistency. Operations in each threads appear in the same order as defined in the program. However, they can be interleaved with operations from other threads, but all them, taken globally, are executed sequentially. Any runtime ordering of operations (also called a history) can be explained by a sequential ordering of operations.

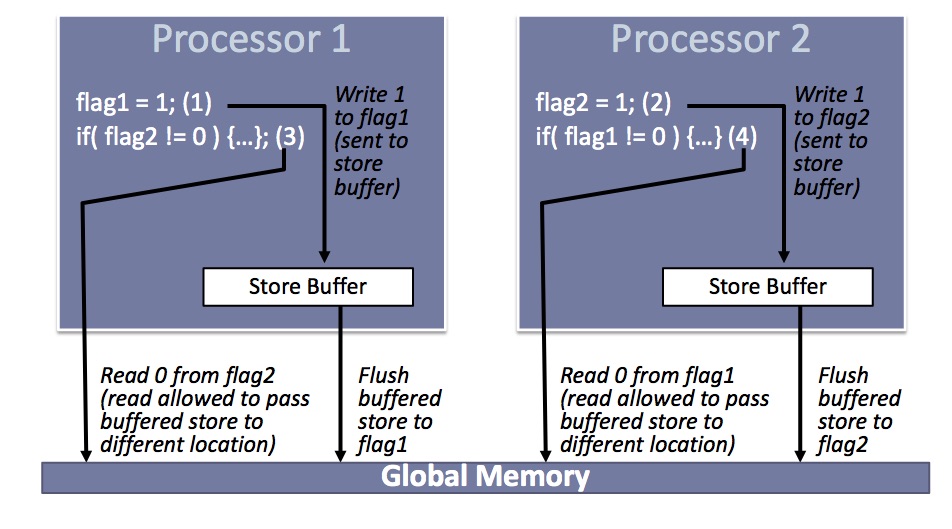

Unfortunately, sequential consistency alone does not guarantee data race free code, as it can be cracked relatively easily in the absence of cache coherence or even in the presence of architectures without cache. In this latter case, the compiler itself can break the sequential consistency through a simple optimization as code reordering.To get this point, see the example below with the famous Dekker’s algorithm for critical sections:

bool flag1 = false;

bool flag2 = false;

//THREAD #1

flag1 = true;

if (flag2 != 0) {

//critical section

}

...

//THREAD #2

flag2 = true;

if (flag1 != 0) {

//critical section

}

...

Write buffers with bypassing, credit Herb Sutter

To comply with Sequential Consistency, we need a cache coherency protocol to make sure that a write is made visible to all cores. Moreover, writes to same location X should appear to be seen in the same order by all cores. We need also a mechanism to detect the completion of write operations and the illusion of atomic read and writes.

The memory model adopted in C++ is sequential consistency for data-race-free programs, shortly SC-DRF. It can be understood as a kind of virtual deal between the programmer and the system. If the programmer agrees to write code that does not have data race, ie is properly synchronized, the system is committed to providing the illusion of executing that program. The good news is both hardware manufacturers and programming languages designers have reached a convergence on the SC-DRF: Java uses this model since 2005 (Java 5), while C11 and C ++ 11 adopt it by default.

Sequential consistency is rather expensive to implement on some architectures, that’s the reason relaxed memory model are adopted. In a nutshell, using memory barriers are used that ensure that operations are totally ordered but only partially ordered.

###Summary Modern multi-core CPUs are extremely sophisticated. Cache layers are a largely adopted solution to minimize the difference in performance between CPUs and memories. Moreover, with the aim of maximize speed execution, a modern multicore CPU tries a lots of ways: store buffers, branch predictions, pre-fetching, speculation, out-of-order execution, hyper-threading. Every single core is definitely a very powerful resource, but for taking full advantage of it, we need design concurrent applications.

Unfortunately, concurrency is notoriously hard. A new class of programming errors happen, beyond those all too familiar in sequential code. Data races, deadlock and livelock arise from bad synchronization. And also when these errors are not present, bad concurrency can be a performance bottleneck: lock contention, cache coherence overheads, and lock convoys, are difficult to identify with simple profilers. Write efficient concurrent programs requires a well domain knowledge, efficient data structures, ie lock-free or wait-free, and smart programming tools.

Actually, the compilers also perform code transformation to speed up code execution. However, in a multi-thread environment, many commons code optimizations end in adding a data race. In these situations is very hard to reason when transformation made by compiler are safe or not. To deal with this complexity, hardware vendors, researchers and working-groups all around the worlds, put toghether their efforts to guarantee that any kind of optimization (hardware or software), must be thread-aware. Actually, the most used modern programming languages, ie Java and C++, use memory models.

Memory synchronization actively works against important modern hardware optimizations - Herb Sutter

A memory model, or memory consistency model, constrains the transformations that any part of a system, ie compiler/JIT or CPU, may perform. Sequential consistency, defined by Leslie Lamport, is the most intuitive memory model. It ensures that memory operations in all threads appear to occur in a single total order. Further, within this total order, all memory operations of a given thread appear in the program order for that thread. The biggest problem of sequential consistency model is that it is too much restrictive and the speed execution is quite slow. It blocks many common optimizations and, as a consequence, it can become a performance bottleneck. An alternative approach proposed to preserve the sequential consistency’s simplicity and to overcome its performance limitations, which is the one used by Java and C++, is the so called data-race-free model. This model introduces the notion of correct programs as those that do not contain data races, ie are well synchronized. It guarantees sequential consistency for programs without data races and has undefined semantics in the presence of a data race. The first consequence of the adoption of a memory model, is that is not cost-free. Programmability and performance are clearly affected, because now any part of the system that makes transformation must respect some contraints specified by the memory model.

In Part 2, I’m going to dive in the C++ memory model and provide some examples on the use of atomic types available in the standard library.

##Further Information Foundations of the C++ Concurrency Memory Model, by H.Boehm, S.Adve

Abstraction and the C++ machine model, by Bjarne Stroustrup

Memory model for multithreaded C++, by Hans-J. Boehm

Memory model for multithreaded C++: Issues by A.Alexandrescu et al.

Memory Ordering in Modern Microprocessors, Part I, by Paul E. McKenney, Linux Journal

Memory Ordering in Modern Microprocessors, Part II, by Paul E. McKenney, Linux Journal

Who ordered memory fences on an x86?, by Bartosz Milewski, Bartosz Milewski’s Programming Cafe

Lock-Free Algorithms For Ultimate Performance, by Martin Thompson

Software and the Concurrency Revolution, by H. Sutter and J. Larus