C++ Memory model for effective concurrency. Part II

My previous post provided a brief overview of memory models and why they are so important to write efficient code in a multi-threaded system. Among developers, is a common opinion that is not essential dive into C++ memory model for peole who generally uses mutex and locks to achieve data-race free programs. However, in my opinion, anyone who is involved in designing a high-performance software system, need know one of the memory model among Java an C++ at least. Memory models are a treasure of extremely useful ideas for programming.

###The C++ memory model

####Memory Object Layout C++ is system language. Is not required adopt another low-level language to be close to the machine. For historical reasons, it born as hardware-friendly programming language. Nowadays, it is still hardware friendly, but includes also a superb set of powerful abstraction models. I dare to say that C++ is total language: cause you don’t need nothing more. C++ provides many tools to be closest to the hardware, such as atomic types and facilities for low-level synchronization. This permits a reduction of the number of CPU instructions and the number of system calls to the operating system for resolving contentions among threads.

To understand how C++ memory model works, we need start looking at the way data are stored in memory. In C++, all data are made by objects. But beware, in this context, when the word object is used, there is any referring to object in Object-Oriented Programming. They are different things.

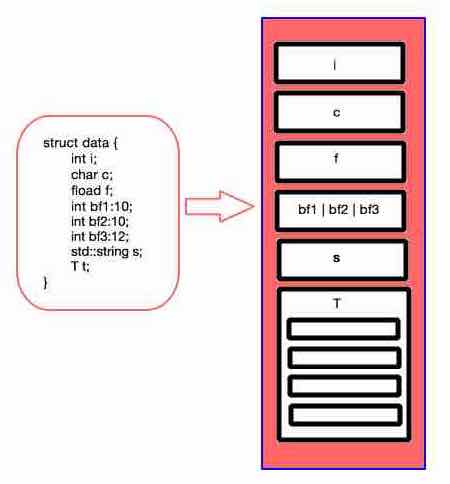

The C++ Standard defines an object as a region of storage. These objects can be fundamental data type such as integer or float, or user-defined types. The important concept to grasp here, is that every object is saved in one or more memory locations, no matter its specific type. Each one occupies at least one memory location.

In the example below, the struct data is a single object composed by more sub-objects. Each object has its own memory location. Fundamental types, for example int, char or float, occupy a single memory location, while composed types are made by more objects and, obviously by more locations. Bit fields are an exception: from a programming point of view they are considered separate entities, but in a memory model context they are considered the same ‘object’ because they share the same memory location.

Memory Object Layout

Threads do their job accessing these memory locations. If they work on different locations, all is well. Conversely, if they need access the same location and at least one thread is going to write data, the access must be synchronized to avoid partial modifications and data corruption. Access ordering can be obtained using locks and atomic variables. When any synchronization mechanism is adopted, a program enters into the limbo of undefined behavior. At that point all bets are on, even that the PC will merge and in its place will appear a Rolex :).

In a program execution, all write operations made by all threads on that specific object define its modification order. To ensure data-race free programs in a multi-threading system, all threads must agree on this modification order. In particular, every read operation from a memory location must always return the last data written in. The first consequences, is some kind of speculative execution are no more valid.

####Example 1 Given two global variables pressure and temperature:

uint8_t pressure;

uint8_t temperature;

...

//Thread 1

{

std::lock_guard(pressure_mutex);

pressure = 5;

}

//Thread 2

{

std::lock_guard(temperature_mutex);

temperature = 23;

}Say the compiler lays out the two variables contiguously, and transforms the assignment temperature = 23 to:

uint8_t tmp[4];

memcpy(&tmp[0], &pressure, 4);

tmp[1] = 23;

memcpy(&pressure, &tmp[0], 4); // oops... write sharing data without holding a lock!Can you see where the problem here? It’s the virtual assignment pressure = pressure. It is not an harmless as you could image. I’s a write operation on a shared data made without holding a lock! In C++11, this kind of optimization is not permitted, so there are no data races, while old compilers are free to use this kind of optimization.

####Example 2 This time let’s put the pressure and temperature inside a global variable data:

struct {

uint8_t pressure;

uint8_t temperature;

} data;

...

//Thread 1

{

std::lock_guard(pressure_mutex);

data.pressure = 5;

}

//Thread 2

{

std::lock_guard(temperature_mutex);

data.temperature = 23;

}Again, say the compiler lays out the two variables contiguously, and transforms the assignment temperature = 23 to:

uint8_t tmp[4];

memcpy(&tmp[0], &pressure, 4);

tmp[1] = 23;

memcpy(&pressure, &tmp[0], 4); // equivalent to pressure = pressureAlso in this case, an old compiler could introduce a write that was not present in the original source code and that breaks the mutual exclusion. In C++11, compiler cannot do this optimization in a multithreaded program.

####Example 3 This time pressure and temperature are defined as bitfields:

struct {

int16_t pressure:10;

uint16_t temperature:6;

} data;

...

//Thread 1

{

std::lock_guard(pressure_mutex);

data.pressure = 5;

}

//Thread 2

{

std::lock_guard(temperature_mutex);

data.temperature = 23;

}Reminds, I said in C++11 adjacent bit fields are considered the same object. In other words, it may be impossible generate code that will update the bits of temperature without updating the bits of pressure, and vice versa. There is a data race here, also in C++11.

This is one of the side effect of memory models in programming languages like C++ or Java. They constraint the kind of optimizations that can be made at various levels that lead to the program execution, avoiding the risk of introducing unsafe hidden writes in the code.

The compiler must never intevent a write to a variable that wouldn’t be written to in a an SC execution - Herb Sutter

###Atomic operations An atomic operation is indivisible, ie it cannot be partially executed. It’s like it completes or is not executed at all. Is not experience a partial read or write with atomic variables. In C++, many atomic types are natively, meaning that atomicity is supported by CPU. In other cases, is the compiler that put a lock to ensure the atomicity of the operation. For this reasons, every atomic types have a is_lock_free() method which can be used to verify the implementation.

The atomic types are all defined in the header atomic<> The simplest is std::atomic_flag, which is in fact a boolean flag. It can be only in two states, clear or set, and needs to be initialized with ATOMIC_FLAG INIT. It is a kind of type thought to be used as building block. Indeed, it is the only one for which is guaranteed a lock free implementation. clear() cleans up the flag, while test_and_set() sets the flag and returns the old value. Below, an example of how std::atomic_flag can be used to achieve a mutex with active waiting. If test_and_set()returns false, it means that the mutex has been acquired:

#include <atomic>

class spinlock_mutex

{

private:

std::atomic_flag flag;

public:

spinlock_mutex() : flag(ATOMIC_FLAG_INIT) {

}

void lock() {

while (flag.test_and_set());

}

void unlock() {

flag.clear();

}

};One of the common aspects of all atomic types, is they can not be copied or assigned between them. It is a fairly simple concept. Copying and assignment operation involve two objects. Inside a copy constructor and copy assignment, a value has to be read and copied from one object to another one. These are independent operations on two distinct objects, and there is no way to make their combination atomic.

std::atomic_flag is so simple that it can not be assigned to another std::atomic_flag or even set. For this purpose, there is *std::atomic

std::atomic<bool> flag;

flag.store(true);

bool f = flag.exchange(false);compare and exchange operations are probably the most common operations used with atomic types. Simply put, the value stored in an atomic variable is compared against a predicted value provided by the programmer. The desired value is stored only if the expected value matches the current value stored by the atomic variable. If not, the expected value is set to the actual stored value.

compare_exchange_weak() is called this way because occasionally may return false even when the expected value is equal to the stored value. This phenomenon is called spurious failures and implies that compare_exchange_weak() need to be used in a loop. spurious failures happen because of CPU architecture that does not support atomic operations natively.

//A shared variable

atomic<bool> flag;

...

bool expected = false;

//set to true

while(!b.compare_exchange_weak(expected, true)) && !expected);

...

//set to false

expected = true;

while(!b.compare_exchange_weak(expected, false)) && expected);The template std::atomic<T> is used for user-defined atomic types. However, there is a limitation: it’s possible use only types with a trivial copy-assignment operator and bitwise equality comparable. Indeed, the compiler must be able to make copies using memcpy and comparisons with memcmp.

###Synchronized operations and ordered access

Consider the piece of code below. It’s a very easy program. Say read() and write() are executed by two threads: how can we guarantee that the sequence of operations (1), (2), (3), (4) is always achieved?

//A shared variable

atomic<bool> data_ready;

T data;

void read() {

while (!data_ready.load()); (3)

//consume data ... (4)

}

void write() {

//write data ... (1)

data_ready.store(true); (2)

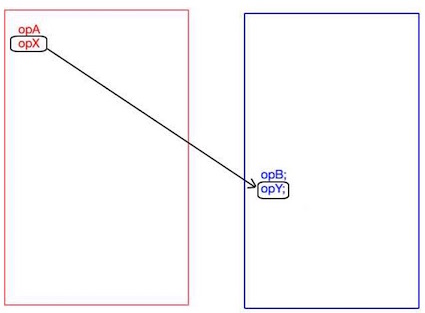

}Reminds that thread can be executed on separated CPUs, and different CPUs could have different default ordering constraints on basic operations such as load and store. In other words, we would like to have something that permits to say: if opX synchronizes with opY, then opA happens before opB.

How C++11 can help to solve this issue? The ordered access can be obtained thanks to locks and atomic types which provide the necessary order thanks to memory model’s virtues. In particular, in C++11 we need start thinking about things in terms of happens-before and synchronizes-with, two new relationships introduced with memory model.

Synchronizes-with and happens-before relationships

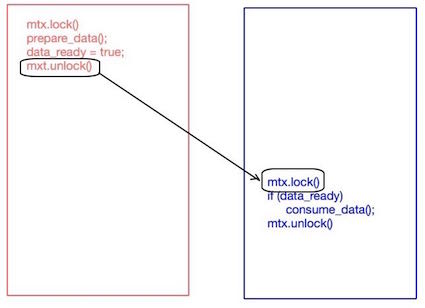

Mutex are the most common way for providing inter-thread synchronization: unlock()synchronizes with calls to lock() on the same mutex object.

Synchronizes-with and happens-before relationships using mutex

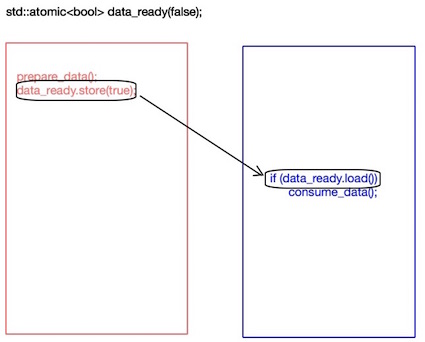

std::atomic<> is the other way for providing inter-thread synchronization. However, differently from locks, it needs hardware support (not all architecture provide lock-free atomics). In this case, a store to a memory location synchronizes with a load from the same location.

Synchronizes- with and happens-before relationships using atomic<>

####Happens-before The happens-before relationship is at the base for instructions ordering in a program. It specifies what operations see the effects of other operations.

From C++11 Standard

An operation A happens-before an operation B if:

- A is performed on the same thread as B, and A is before B in program order, or

- A synchronizes-with B, or

- A happens-before some other operation C, and C happens-before B.

In a single-thread program, the happens-before relationship is fairly trivial. If an operation A is written in the code before another one B, then A happens before B. Back to our example, we can say that (1) happens before (2) and (3) happens before (4).

####Synchronizes-with The synchronize-with relationship can be obtained using atomic types and locks (which use atomic types implicitly).

From C++11 Standard

An operation A synchronizes-with an operation B if A is a store to some atomic variable m, with an ordering of std::memory_order_release, or std::memory_order_seq_cst, B is a load from the same variable m, with an ordering of std::memory_order_acquire or std::memory_order_seq_cst, and B reads the value stored by A.

Put simply, if thread A writes a value X and thread B reads the value of X, therefore there is a relationship synchronize-with between the writing and the reading thread. Back to our example, we can say that (2) synchronizes with (3).

Thanks these two relationships, we can say that events occur in sequence: (1), (2), (3), (4).

###Memory ordering for atomic operations In C++11 there are three different memory models: sequential consistency ordering, acquire-release ordering, and relaxed ordering. They have different costs depending from specific CPU architecture. acquire-release and relaxed ordering are just two degrees of relaxation of sequential consistency. They are more difficult, but when used properly can produce very efficient code. To use a specific model, is necessary to tag every load and store operation with a specific tag (reported in the enum below). memory_order_seq_cst is the default ordering model, so it can be omitted.

namespace std {

typedef enum memory_order {

memory_order_relaxed,

memory_order_consume,

memory_order_acquire,

memory_order_release,

memory_order_acq_rel,

memory_order_seq_cst

} memory_order;

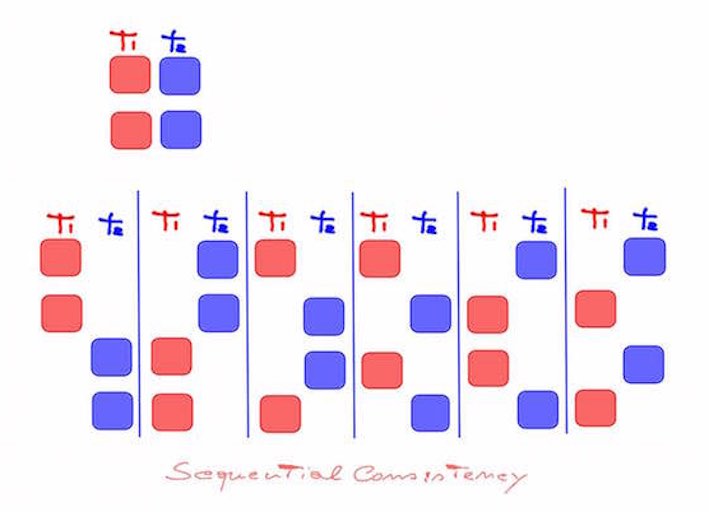

}###Sequential consistent ordering The default ordering is called sequential consistency as it implies the program behavior is consistent with a sequential view of the world. This means if all operations on atomic variables are sequentially consistent, the behavior of a multithreaded program is the same as if all operations are executed in a specific sequence within a single thread. sequential consistency is the default ordering because of its simplicity to understand and reasoning about code that uses atomic types.

Sequential consistency

However, this simplicity is not cost-free. On multi-core cpu or multiprocessor system with a weak ordering model, sequentially consistent can result in a performance penalty, because of operations must be kept consistent between all cores.

Synchronization operations can be quite expensive. That said, it should be remembered that some architectures like x86 and IA64* offer sequential consistency without big extra costs. Architectures like **ARM7* or **Power, however, experience a significant reduction in performance.

The default value for all operations on atomic variables is memory_order_seq_cst, that similarly to Java’s volatile, force sequential consistency. The program reported above is equivalent the following one, where memory_order_seq_cst has been reported explicitly.

//A shared variable

atomic<bool> data_ready;

T data;

void read() {

while (!data_ready.load(memory_order_seq_cst)); (3)

//consume data ... (4)

}

void write() {

//write data ... (1)

data_ready.store(true, memory_order_seq_cst); (2)

}###Non-Sequentially consistent memory ordering To avoid synchronization cost, we must exit out of the world of sequential consistency and start considering different memory order models. And here things get complicated quickly. For a simple reason. There is more than a single global order for all events. In this context, different threads do not necessarily agree on the order of events, because of CPU internal cache levels and store buffers. Threads do not need to agree on total order, but the only requirement is that all threads agree on the changing order of every atomic variable.

####Relaxed ordering Atomic operations must be tagged with memory_order_relaxed. Store and load operations do not participate in the synchronizes-with and happens-before relationships. The only requirement is that within a single thread all operations on the same variable continue to obey the relationship happens-before. Operations on different variable can be reordered and there is no guarantee about the ordering seen by other threads.

So in relaxed ordering memory model, the accesses to an atomic variable can not be reordered.Simply put, the reading of an atomic variable X must always return the last value written to X, while the relaxed operations on different variables can be sorted freely. As already mentioned, there is no synchronizes-with relation, so , this relaxed ordering works well only in situations where publishing operations are not required. Consider the code below where load and store have been tagged with memory_order_relaxed. In this case, there is nor synchronizes-with nor happens-before relationship between operation on different variable, so we don’t have any guarantee that the sequence of operation (1), (2), (3), (4) is always guaranteed.

atomic<bool> data_ready;

T data;

void read() {

while (!data_ready.load(memory_order_relaxed)); (3)

//consume data ... (4)

}

void write() {

//write data ... (1)

data_ready.store(true, memory_order_relaxed); (2)

}####Acquire-release ordering This is a step forward compared to relaxing ordering, but still quite far from sequential consistency. For acquire-release orderin model there is a global ordering for all the operations. However, it introduces a light form of synchronization. In this case, loads are acquire operations (memory_order_acquire), while stores are release operations (memory_order_release). Other operations as fetch_add() and exchange() may be acquire, release or both. In this model, a release operation synchronizes-with an acquire operation. In this way, different threads continue to see a different ordering, but there is still a limited number of combinations because of constrains imposed by synchronizes-with relationship.

atomic<bool> data_ready;

T data;

void read() {

while (!data_ready.load(memory_order_acquire)); (3)

//consume data ... (4)

}

void write() {

//write data ... (1)

data_ready.store(true, memory_order_release); (2)

}memory_order_consume is part of acquire_release model, but it is very, very special. In fact, it is about data dependencies. Dealing with data, new kinds of dependencies are introduced: carries-a-dependency-to which applies in single thread and models data dependencies among operations. If the result of an operation A is used as operand in another operation B, then A carries-a-dependency-to B.

The relationship depedency-ordered-before applies between threads. It is introduced using atomic load operations tagged with the attribute memory_order_consume. It is a special case of memory_order_acquire that limits the data synchronized to a direct dependence: a read operation tagged with memory_order_release, memory_order_acq_rel, or memory_order_seq_cst is depedency-ordered-before a load operation B tagged with memory_order_consume if the consumer reads the saved value. An important use for this kind of memory sorting is when a load operation loads a pointer. Using memory_order_consume for the load and memory_order_release for the store, it is guaranteed that the pointer is synchronized, without imposing any restriction on other unnecessary data.

atomic<bool> data_ready;

T data;

void read() {

while (!data_ready.load(memory_order_consume)); (3)

//consume data ... (4)

}

void write() {

//write data ... (1)

data_ready.store(true, memory_order_release); (2)

}###Fences As conclustion, it worth to mention fences, which are commonly called memory barriers. These are operations which place constraints on the organization in memory without changing any kind of data. They are generally used with memory_order_relaxed. They put special instructions in the program that certain operations can not overcome. We have already said that relaxed operations on different variables can be rearranged without any constraint. The fences limit this freedom imposing constraints and introducing relations as happens-before and synchronizes-with that were not present before. They are specified in std::atomic_thread_fence.

##Further Information

C++ Concurrency in Action: Practical Multithreading, by Anthony Williams

Foundations of the C++ Concurrency Memory Model, by H.Boehm, S.Adve

Abstraction and the C++ machine model, by Bjarne Stroustrup

Memory model for multithreaded C++, by Hans-J. Boehm

Memory model for multithreaded C++: Issues by A.Alexandrescu et al.

Memory Ordering in Modern Microprocessors, Part I, by Paul E. McKenney, Linux Journal

Memory Ordering in Modern Microprocessors, Part II, by Paul E. McKenney, Linux Journal

Who ordered memory fences on an x86?, by Bartosz Milewski, Bartosz Milewski’s Programming Cafe

Functional Data Structures and Concurrency in C++, by Bartosz Milewski, Bartosz Milewski’s Programming Cafe

Lock-Free Algorithms For Ultimate Performance, by Martin Thompson

Software and the Concurrency Revolution, by H. Sutter and J. Larus

How does Java do it? Motivation for C++ programmers, by Bartosz Milewski, Bartosz Milewski’s Programming Cafe

Peterson’s lock with C++0x atomics, by Antony Williams, Just Software Solutions

Multicores and Publication Safety,by Bartosz Milewski, Bartosz Milewski’s Programming Cafe